While you're opening your Valentine Day Cards and eating your special candy, opine on this -

When Rome was first founded, wild and bloodthirsty wolves roamed the woods around the city. They often attacked and mauled and even devoured Roman citizens—which, incidentally, is why the city took more than a day to build.

With characteristic ingenuity, the Romans begged the god Lupercus to keep the wolves away. Lupercus was the god of the wolves, so he was expected to have some influence on their behavior.

He didn't.

Wolves kept attacking and Romans kept dying.

This led the Romans to the obvious conclusion that Lupercus was either angry or away on business. It was a serious problem either way. Now, to this point in their history, the Romans had addressed all of their problems with one of two solutions: the first was to pray to their gods. Okay, they'd tried that. It didn't always work.

The second solution was to get drunk out of their minds and have an orgy.

So, in an effort to get their slacker god's attention, they had a huge party in his honor. They called it Lupercalia. It was an early April holiday celebrated on February 15 because, in spite of their classical educations, the Romans were as bad at reckoning months as they were at building roads—it was impossible to leave the city, for example, because all their roads led right back to Rome.

Because it was a spring holiday, and because Lupercus either didn't know or didn't care how many Romans were devoured by wolves, and because the Romans weren't wearing anything under their togas, Lupercalia gradually became a kind of swingers' holiday.

On Lupercalia Eve, Roman girls would write their names on slips of paper that were placed into a big jar. The next day, every eligible young man in Rome withdrew a slip of paper from the jar, and the girl whose name he had withdrawn became his lover for the year. Also on the eve of the Roman feast, naked youths would run through Rome, anointed with the blood of sacrificed dogs and goats, waving thongs cut from the goats. If a young woman was struck by the thong, fertility was assured. Much grab-ass ensued.

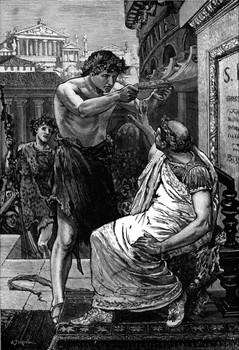

Marc Anthony, naked and gore drenched, after a crazed run through the Roman Forum on the feast of Lupercalia, offered Julius Caesar the imperial crown of Rome. Caesar demurred and told Marc Anthony to go home, take a shower and get dressed.

As an interesting aside, they would often sew their lovers' names on their sleeves, from which we get the expression, who the hell taught you how to sew? Also, this must have been one hell of a party.

Romans were still attacked and killed by wolves, but no one really gave a damn now that they were all getting laid.

The festival endured.

Hundreds of years went by.

In the early years of Christianity, the Roman Emperor Claudius II was having problems with his army. Many of his soldiers were married men, and they couldn't be convinced that marching off to god forsaken barbarian backwaters to kill disgusting savages was more important than staying home and having sex with their wives.

Claudius ordered his soldiers not to get married. To be absolutely safe, he ordered priests not to marry soldiers. Not many soldiers wanted to marry priests, so this wasn't a big problem (some of the soldiers would have been happy to marry other soldier but that's another story.)

Now, there was one old priest who thought the emperor's policy was unfair. It wasn't so much that he wanted to marry any soldiers—he enjoyed playing the field—but he felt that he ought to be able to perform the holy rite of matrimony for soldiers who wanted to marry women (and be tipped accordingly - remember this is the Catholic Church - nothing happened unless you remember to tip your priest.) He began conducting secret Christian marriages.

The old priest was quickly arrested and imprisoned. On Lupercalia Eve of 270 AD—that's February 14, remember—he was decapitated.

That priest's name was, of course, Marius.

Arrested, imprisoned, and beheaded right alongside him, however, was another priest who'd been performing secret marriages—a handsome young priest named Valentine.

We don't know much about ole Valentine, but there are a lot of apocryphal stories. There's one about how, while he was in prison, Valentine fell in love with the blind daughter of his jailer and eventually taught her to see. There's another one about Claudius being so moved by Valentine's eloquent defense speech that he offered to call off the execution if the priest would abandon Christianity. But there's also a story about an old lady putting her dog in the microwave ... and you don't see me going off on that tangent. As time went on, people forgot about old Marius, who hadn't been very photogenic. People remembered the handsome Valentine, and eventually he was canonized.

There was a new saint in town—St. Valentine.

And, like most saints, he'd been dead for years. But for all the fuss over what he did while he was alive, he has been absolutely spectacular in death.

His relics are on display today at St Francis's Church in Glasgow, Scotland. They can also be seen at the Whitefriar Street Church in Dublin, Ireland. They're also at the Church of Saint Praxedes in Rome and the Collegiate church of Saint Jean-Baptiste and Saint Jean l'Evangéliste in Roquemaure, France, as well as eight other churches, two cathedrals, and all over Ebay. The Raelians could learn a thing or two from this dead saint.

If you do the math and were to gather all of St. Valentine's remains from all these churches, you'd have enough raw material for three new bishops, two deacons, and a linebacker. Giving eyesight to the blind is impressive, but as saints go it's the equivalent of a card trick. Multiplying your remains after you're dead, though. . . there's a miracle.

But, as the French say, let us return to our sheep.

(And let's not ask what the French intend to do with their sheep.)

One day the Christian Church took control of the calendar, which the Romans had reduced to one long series of overlapping holidays. The Christians moved Lupercalia back a day and renamed it St. Valentine's Day. No one objected to this change, since Lupercus still hadn't saved a single freaking soul from the wolves and the Romans still weren't wearing anything under their tunics.

And so St. Valentine's Day came to be celebrated as a harbinger of spring, a glorious tribute to the romantic splendor of Christian marriage, and a time for some good old-fashioned pagan fornication.

More centuries passed.

Christianity became more widespread, the calendar was finally perfected, and the holiday evolved into what it is today: a glorious midwinter celebration of passion, romance, and toe-curling sex. In some countries it's also celebrated by married couples.

(It should be noted that St. Valentine was removed from the Christian Calendar in 1969 because the church could not abide one of its sacred holidays being so flagrantly commercialized.)

Valentine's Day Cards

Let's go back for a moment to another apocryphal story about Marius' good friend Valentine.

On the day he was finally led to his execution, the jailer's daughter - the blind girl he'd taught to see--couldn't bear to say goodbye. Valentine understood, naturally—he had the patience of a saint—so he said goodbye in a letter. He signed it, "From your Valentine."

"The phrase," one source informs us, "has been used on his day ever since."

But that's not true. I should have known it wasn't true, since the source happened to be the guy sitting next to me in a bar where I did all my research.

The first true Valentine Card—and by that I mean the first such card signed by anyone whose name wasn't actually Valentine - was sent in 1415 by Charles, the Duke of Orleans, to his wife.

The Duke had been captured at the battle of Agincourt and was locked up in the Tower of London, and probably wasn't trying to be romantic so much as clever. Signing a love-letter "Your Valentine" didn't mean "your adoring spouse" or "your loving boo-boo." It meant, "your husband, still in jail, probably about to have his head chopped off."

Two-hundred-and-fifty years later, Samuel Pepys, who was probably familiar with the whole Duke of Orleans thing, wrote romantic poems to his wife on Valentine's Day and signed them "Your Valentine." Since he was neither in jail nor about to have his head chopped off, this was probably the first real Valentine.

Today, of course, billions of Valentines are exchanged each year, many of them from people not in jail or facing decapitation.

And so it goes.

No comments:

Post a Comment